Science

Archaeologists Assess Indigenous Long-Distance Voyaging Evidence Below 50°S

Recent research led by Dr. Thomas Leppard and his team has examined the potential for pre-European long-distance voyages by Indigenous peoples in the Southern Hemisphere, specifically below the 50th parallel. Their findings, published in the Journal of Coastal and Island Archaeology, indicate that while there is no evidence of such voyages before European contact, this is attributed to the hazardous environmental conditions rather than a lack of seafaring capability.

The Southern Ocean, which lies south of the 50th parallel, is notorious for its harsh climate, characterized by fierce winds, extensive ice sheets, and freezing temperatures. Many islands located in this region, including those in the Subantarctic, are largely uninhabitable, with minimal flora and fauna beyond seals and seabirds. Historically, it was believed that these islands were largely uninhabited prior to European exploration, except for areas like Tierra del Fuego in South America.

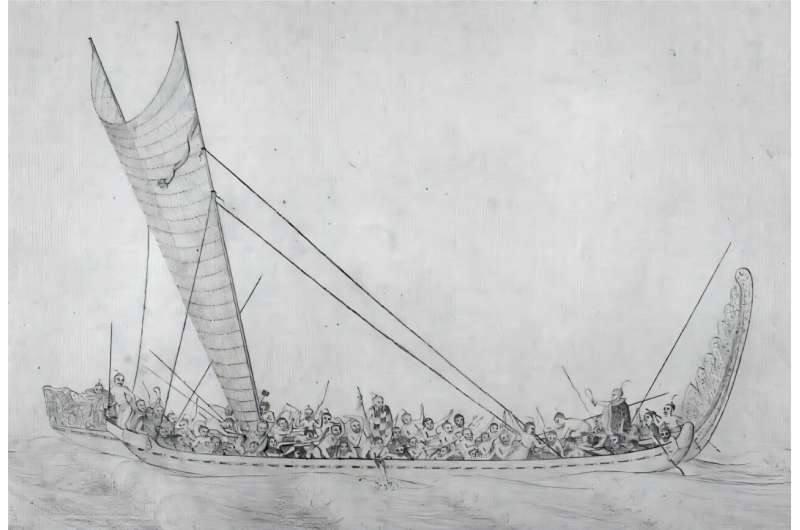

Recent discussions have suggested that these islands may have been known to Indigenous peoples long before European arrival, a notion that could reshape our understanding of Indigenous navigation and seafaring technology. The Māori, known for their exceptional navigation skills, inhabited New Zealand and its nearby islands. There are accounts, such as those documented by Stephenson Percy Smith in 1899, suggesting that a legendary navigator named Ui-te-Rangiora may have reached Antarctica. However, the evidence for this claim remains tenuous, particularly given the linguistic challenges in interpreting ancient terms related to ice and cold.

To assess these claims, the researchers focused on islands south of the 50th parallel that show signs of human habitation, particularly Enderby Island. This island, settled around 1300–1400 AD, was abandoned due to deteriorating climate conditions. Despite this, no signs of human presence have been found on the southern islands, leading researchers to conclude that the extreme living conditions would have made further southward habitation unfeasible.

The team speculates that the challenges of securing necessary resources for ship repair and supplies would have further complicated any potential voyages. The wood needed for repairs could only be sourced from the Auckland Islands, while flax for sailing materials was available only in New Zealand. The limitations of using materials like bark or sealskin for longer journeys would have rendered such expeditions impractical and perilous.

Dr. Leppard notes that, apart from the Rarotongan oral traditions, there is a notable absence of stories or records indicating any significant voyages into the Southern Ocean. He states, “We have not found any other oral histories of southern voyaging, and we would not expect them because no offshore seafaring technology comparable to that in Polynesia was recorded in Australia or southern South America.”

The investigation also explored whether Indigenous peoples from South America had settled on various islands, including the Falkland Islands and the South Shetland Islands. Although some artifacts have been linked to Indigenous populations, these are primarily associated with post-European contact activities. For instance, the transfer of 150 Indigenous individuals to Pebble Island in 1855 resulted in the creation of whalebone harpoons and stone tools, but these do not provide evidence of pre-contact habitation.

The maritime technology utilized by Indigenous peoples in southern South America was tailored for navigating inland waterways rather than the open ocean. These vessels were typically small and vulnerable, making any attempts at long-distance travel risky. The absence of archaeological evidence prior to European contact is striking, especially considering the cold conditions that would usually foster better preservation of organic materials.

Dr. Leppard emphasizes the significance of this lack of evidence, stating, “In these environments, we’d actually expect organic materials to preserve better. Cold conditions inhibit decay, while warmer conditions exacerbate it.” He adds that the limited modern development on these islands would likely mean that any archaeological record should still exist if it were present prior to European contact.

The researchers conclude that given the high risks and low chances of survival associated with voyages into these harsh environments, such undertakings were likely never attempted. Nonetheless, they remain open to new data that could challenge their findings. Dr. Leppard expresses optimism for future studies, stating, “While we’re not planning another collaborative paper on the Antarctic in the near future, we look forward to continuing to work on issues of colonization, seagoing, and island adaptations.”

This research contributes to an evolving understanding of Indigenous maritime culture and the potential for historical seafaring in some of the world’s most challenging environments.

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoDiscover the Top 10 Calorie Counting Apps of 2025

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoBella Hadid Shares Health Update After Treatment for Lyme Disease

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoErin Bates Shares Recovery Update Following Sepsis Complications

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoDiscover 2025’s Top GPUs for Exceptional 4K Gaming Performance

-

Technology2 months ago

Technology2 months agoElectric Moto Influencer Surronster Arrested in Tijuana

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoDiscover How to Reverse Image Search Using ChatGPT Effortlessly

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoMeta Initiates $60B AI Data Center Expansion, Starting in Ohio

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoRecovering a Suspended TikTok Account: A Step-by-Step Guide

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoTested: Rab Firewall Mountain Jacket Survives Harsh Conditions

-

Lifestyle4 months ago

Lifestyle4 months agoBelton Family Reunites After Daughter Survives Hill Country Floods

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoUncovering the Top Five Most Challenging Motorcycles to Ride

-

Technology4 months ago

Technology4 months agoHarmonic Launches AI Chatbot App to Transform Mathematical Reasoning